Our History

Origins

Phillips Brooks House was constructed in the memory of the Reverend Phillips Brooks, a preacher at Trinity Church, Harvard graduate, and advocate for social service. Plans for the building were drafted and completed upon Brooks’ death in 1893, and Phillips Brooks House was dedicated on January 23, 1900, to serve “the ideal of piety, charity, and hospitality.”In 1904, six organizations formally organized themselves into the Phillips Brooks House Association (PBHA), and by the 1920s all of the religious groups had withdrawn from the organization. The Social Service Committee and several offspring philanthropic groups continued to serve the mission of PBHA in a non-sectarian manner.

“Oh, my friends never be ashamed...of optimism. With endless difficulties around us, let us not let our arms drop and be idle. We think that this end of the century is leading into something beyond...there is something in the air that makes us hope.”

1900s-1940s

Early service efforts included placing students at settlement houses, organizing clothing and book drives, and financing missionaries to serve in Asia. During the two World Wars, PBHA volunteer services dwindled, but new services included a Red Cross center, a lounge for ROTC units, and the Harvard Mission Program, which assisted workers in Albania and Turkey. The Great Depression also saw the expansion of local programs, including efforts to teach Harvard courses to local high school graduates who could not afford to attend college.

1950s-1960s

The 1950s marked the beginning of PBHA as we know it today. Many committees began by placing volunteers into existing agencies, but with the help of philanthropic grants, programming activity became increasingly more autonomous. In 1954, students of Radcliffe College were admitted into full participation in PBHA. One of the largest PBHA programs during the 50s was the Mental Health Committee, which placed volunteers in state mental hospitals and exposed students to larger issues of healthcare accessibility and the rights of people with disabilities. By the 1960s, students began to challenge notions of mere "charity" and sought ways to affect social change with their service. "The approach," said former president Michael Robinson '74, "quickly evolved from arms-length charity to an involved attack on basic social and political problems." Volunteers who had previously run recreational programs in Cambridge's Roosevelt Towers got involved with the housing development's tenants' council, advocating around housing issues that affected the youth from those programs. During the 1969 protests on campus, PBHA committed the house to being a common meeting ground. Student activists gathering at the house produced a 12-page report called "The Critique of Harvard Expansion."

1970s

Following the 1960s, PBHA saw a dramatic decline in volunteers as social movements across the nation called for activism instead of service. The students that remained struggled with how to move from charity work that left the status quo unchallenged to true social justice work. Membership plummeted from over 1000 students to less than 200, and the collapse ushered in a time of rebuilding and restructuring.

PBHA was incorporated in 1973. In 1974, PBHA, Inc. began to solicit greater University support. A full-time graduate secretary, now the executive director, was employed for the first time as well. Programmatic efforts were directed at establishing continuity and maintaining a stable internal structure. Mentoring and summer programs in Columbia Point foreshadowed a model of community-based service that would remain foundational to PBHA for years to come, with students providing direct services for youth while working closely with families to understand and advocate around larger issues affecting the community. While membership remained low, the committees formed during this time reflected larger movements for change, including the founding of the Environmental Action Committee, the Committee on Women's Issues, and the opening of Harvard's first women's center on PBH's second floor.

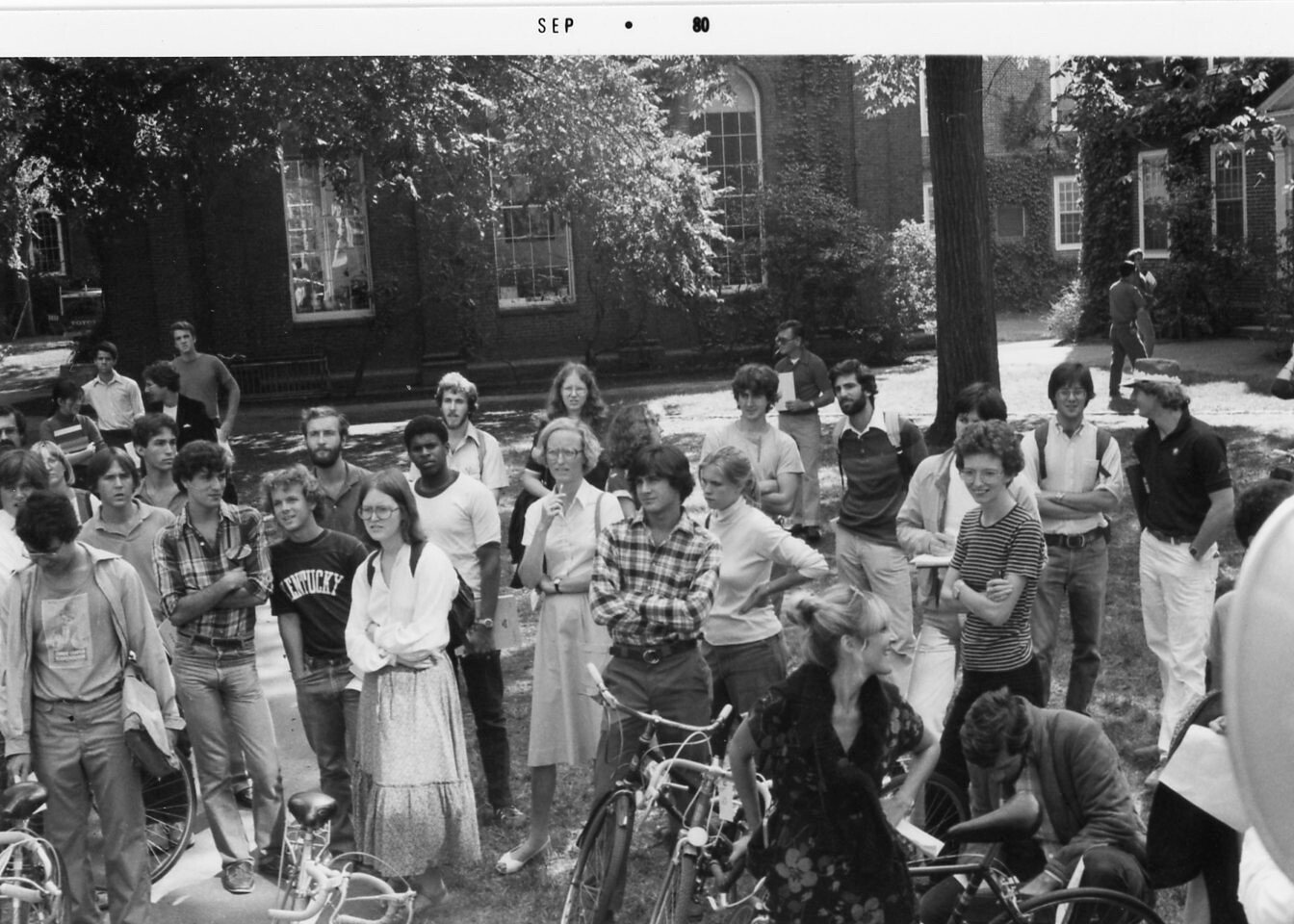

1980s

By the late 1980s, programming had once again increased and committees were flourishing as never before. Programming was initiated throughout Boston and new parts of Cambridge. The Harvard Square Homeless Shelter, housed at the University Lutheran Church (UniLu), opened its doors. A diverse array of programs with interests in education, law, health issues, elderly affairs, advocacy, and youth enrichment began. This was made possible in part by a $1 million capital campaign initiated in 1986. The success allowed the foundation of the association committee, an advisory group composed of alumni, faculty, and community leaders, and the development of the Summer Urban Program (SUP), a 12-camp network providing low-cost summer day camps to more than 700 children in Boston and Cambridge. In response to this rapid growth, the cabinet voted in 1992 to create a student board of directors, charged with managing the corporation’s day-to-day activities to alleviate the time demands on the cabinet’s time.

1990s-2000s

1995 was a pivotal year for PBHA. As Harvard moved towards restructuring the management of the College’s public service activities, it became clear that a gap existed between PBHA’s goals and those of the University. Spurred on by its student leaders, the cabinet passed a resolution in November urging the adoption of “a more rational, autonomous structure” for PBHA. Supported by faculty, the Cambridge and Boston city councils, many community members, and Harvard students, over 2,000 people participated in a rally on December 7, 1995, in support of student voice in public service activities. The rally marked the beginning of a new era for PBHA and was followed in the spring of 1996 by an extensive rewriting of the by-laws. The cabinet’s approval of the new by-laws created a board of trustees for PBHA composed of students, administrators, faculty, alumni, and community leaders. The board is charged with long-term planning for the corporation, while day-to-day management remains in the hands of the cabinet and its elected student officers. In the summer of 1996, an agreement was reached between Harvard College and PBHA allowing this new structure for a one-year trial period. After further negotiations, a final agreement was reached in September 1997. Since then, the board of trustees has hired an executive director, who has in turn brought on a deputy director to support the programming of the organization, and a development director, to help launch a $7.25 million Centennial Campaign.

The nineties were marked by a recurring debate: should service be more political, or less? Officers argued increasingly that working among a particular community requires an awareness of and engagement with that community's history and issues, which often intersected with politics. The Progressive Student Labor Movement (PSLM, a precursor to today's Student Labor Action Movement) became a strong voice for advocacy as they led a campaign for a living wage for Harvard workers. The campaign, which included hiring a plane to fly over commencement waving a banner that read "Harvard Needs a Living Wage" and culminated in a sit-in at Massachusetts Hall, led to wage negotiations and increased hourly pay for both security guards and dining hall workers.

Present Day

PBHA today is comprised of more than 85 programs, with over 1400 volunteers participating in a wide range of service activities. The cabinet, still at the heart of governance of the organization, continues to play an important role in setting and managing the vision for PBHA as we head into our second century.

The last decade has brought an increased focus on quality of programming, with more formalized evaluation, training, reflection, and use of technology to keep up with the times, but some things have not changed. PBHA continues to be a space for students and communities to partner for social change. Just as the social movements and protests of the 1960s challenged students to address structural inequality in their service instead of merely applying "band-aid solutions," today's students explore ways that advocacy and service can inform each other, providing resources while working for change.